Leoncio Vidal Park, or simply Vidal Park is located in the heart of the city of Santa Clara, the capitol of Villa Clara. This park is an important stop not only for locals but also for visitors who come to visit the significant buildings in Santa Clara, especially the Che Guevara Mausoleum, wander around with curiosity, and relax and chat in the cafes surrounding it.

Surrounded by important historical buildings, the park is

also one of the few Wi-Fi hotspots in Santa Clara. The park

is well-lit and is an ideal place to relax at night.

HISTORY

On July 15, 1689, when the town of Santa Clara was officially established, the urban plan prepared decreed that a 1,600-square-meter area be set aside for a park near the planned church. Even though the town's population was under 300 as of 1691, and construction of the park began in 1692 within the boundaries outlined in the plan. However, for a long time, it remained far from a park-like appearance.

The square was known by various names, such as: Plaza de

Armas, Plaza Mayor and Plaza de la Constitución. It took the

latter name while the constitutional regime remained in

Spain. For this purpose, a pyramid was built in 1820. Later,

with the agreement of the residents and the the Town Council

it was demolished when Spain lost its authority on the

island.

Finally, in 1848, gardens were created and the grounds were

paved.

In 1871, the City Council decided to name the park Plaza de

Recreo. It was also ordered to renovate the square because,

until then, it had been a neglected piece of land, overgrown

with wild plants, with few trees, and people were walking in

the accumulated mud.

In 1881, four flowerbeds with statues in the center,

representing the four seasons were added to the park. A

chain was strung between these to prevent carriages from

passing through the park.

On March 4, 1899, with the proposal of councilor Enrique del

Cañal and the decision of the Santa Clara City Council, the

park was named Parque Leoncio Vidal.

During the Republican era, leading up to the Revolution, the

park witnessed numerous protests and student demonstrations,

joined by the public. Even the famous Donkey Perico carried

protest signs, including one written on his fur. Donkey

Perico, freed by his owner upon reaching old age, became

accustomed to wandering the streets of Santa Clara. He began

to follow a similar route daily, knocking on doors with his

front hooves to obtain bread or other food. He earned the

sympathy of the locals, especially the youth. The public

sided with Perico against the police's mistreatment of the

animal, leading to violent protests.

However, the park managed to maintain its status for a long

time as a park with people with colored and white skin

sitting in two separate sections. The park was encircled by

twin sidewalks and a fence was separating blacks and whites.

This problem is resolved after the revolution.

Park Leoncio Vidal was also the scene of intense fighting

during the takeover of Santa Clara by the rebels in 1958. If

you pay attention to the facade of the Hotel Santa Clara

Libre across from the park, you can see bullet holes

remained from that year.

On July 15, 1999 , in commemoration of the 310th Anniversary of the founding of Santa Clara, it was declared a National Monument.

Leoncio Vidal Park is located between Máximo Gómez, Rafael

Trista, Colón and Marta Abreu streets.

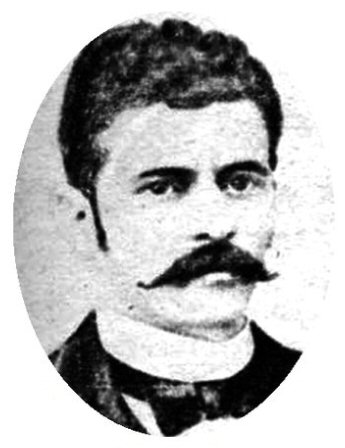

Born in Corralillo, a municipality located in the northwest of the province of Villa Clara, Leoncio Vidal Caro (1864-1896) spent his childhood amidst the struggle for Cuban independence. Fearing the war would spread to them, landowners formed a volunteer unit against the Cuban rebels to protect their land which was joined also by Leoncio's father. However, the innocent murder of a 10-year-old peasant boy by volunteers spurred Leoncio's family to action, and they emigrated to Spain.

In 1978, when the Ten Years' War ended and the Pact of Zanjón was signed, Leoncio's family returned to Cuba and settled in Camajuaní, a town with more opportunities than Corralillo. There, Leoncio and his brothers began publishing El Número 13, a newspaper that reflected their views on the regime. Leoncio and his brothers opposed the exploitation of poor farmers and urged them to join forces to defend themselves against the unfair prices they were being subjected to by buyers and middlemen. They also supported the island's modernization, including the introduction of electricity, the establishment of a fire department, the construction of an aqueduct, and increased literacy.

Increasingly, Leoncio began advocating for the full independence of Cuba, participating in and exchanging views at numerous clandestine meetings held in various venues. At that time, Camajuaní's population was

consisting predominantly of Spaniards, and the infamous Camajuaní Cavalry Regiment, a volunteer unit, was very active.

Knowing that in an imminent conflict, they would be without communication or access to railroads or telegraph, he placed great emphasis on establishing an effective espionage force. He sought out potential collaborators and established a veritable underground army to provide medicine, ammunition, clothing, food, weapons, and timely intelligence. His wife Rosa Caro made extensive use of women for this purpose.

Increasingly, Leoncio began advocating for the full independence of Cuba, participating in and exchanging views at numerous clandestine meetings held in various venues. At that time, Camajuaní's population was

consisting predominantly of Spaniards, and the infamous Camajuaní Cavalry Regiment, a volunteer unit, was very active.

Knowing that in an imminent conflict, they would be without communication or access to railroads or telegraph, he placed great emphasis on establishing an effective espionage force. He sought out potential collaborators and established a veritable underground army to provide medicine, ammunition, clothing, food, weapons, and timely intelligence. His wife Rosa Caro made extensive use of women for this purpose.

In 1891, he founded the Latin Center and began to spread José Martí's ideas. Soon after, he began participating in military actions. Major armed actions involving Leocio in the struggle for Cuba's full independence included the attack on the Vigía Fort, located in the foothills of Santa Fé Hill, in 1895; the attack on the Caibarién train to Cien Rosas to seize supplies in 1895; the attack on the Caibarién train to Cien Rosas to seize supplies in 1895; the battle of Las Yaguas that caused a large number of casualties to the enemy in 1895; machete charge to the Camajuaní guerrilla in San Lorenzo, occupying rifles, machetes and horses in 1896; battle of Palo Prieto led by General Serafín Sánchez, which was the largest and most important battle of Camajuaní on February 8, 1896.

These efforts of Leoncio led him to be promoted to the rank of Colonel within the Mambí Army. The column led by Leoncio Vidal was the only one that was able to penetrate the city, advancing along Santa Clara Street, now Tristá, and was hit by the copious rifle fire of the guards surrounding the square. Colonel Leoncio Vidal Caro lost his life in the attack on Santa Clara at an age of 32 on March 23, 1896.