SANTIAGO DE CUBA

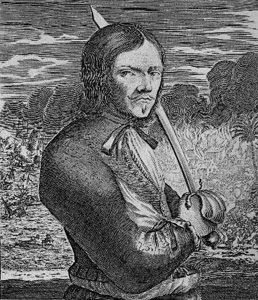

The increasing importance of Santiago de

Cuba and its coasts in commercial point of view was attracting

the pirates since a long time. Jean François de la Roque, François

Leclerc (better known as Pata de Palo, Jacques de Sores, Henry

Morgan, Christopher Mings, Cornelius C. Jo, and the Dutch

Laurens de Graff are among the pirates and corsairs that

plundered Santiago de Cuba from the 16th century to 18th

century.

The first pirate assault on the bay of Santiago took place in

1538. The combat between the Spanish caravel La Magdalena and a

French corsair vessel that had penetrated the Santiago Bay with

the intention of attacking and taking the city, ended with the

victory of the Spanish. It was a strange fight, in that both

captains agreed not to fight at nights and made brief periods of

rest to eat biscuits, to drink wine and to treat the wounds,

although it occurred as a bloody hand-to-hand clash at daytime.

The first pirate assault on the bay of Santiago took place in

1538. The combat between the Spanish caravel La Magdalena and a

French corsair vessel that had penetrated the Santiago Bay with

the intention of attacking and taking the city, ended with the

victory of the Spanish. It was a strange fight, in that both

captains agreed not to fight at nights and made brief periods of

rest to eat biscuits, to drink wine and to treat the wounds,

although it occurred as a bloody hand-to-hand clash at daytime.

During the 16th

century the city was plundered many times by the pirates. These

cruel persons had not any religious belief, so that along with

the rich residences the cathedral has been always in their

target. In 1553 Jacques de Sores attacked the city and demanded

80.000 pesos for not destroying the cathedral. In 1562 the

cathedral’s roof was destroyed by the pirates, and during the

plunder of the city in 1586, the cathedral was set on fire.

During the 16th

century the city was plundered many times by the pirates. These

cruel persons had not any religious belief, so that along with

the rich residences the cathedral has been always in their

target. In 1553 Jacques de Sores attacked the city and demanded

80.000 pesos for not destroying the cathedral. In 1562 the

cathedral’s roof was destroyed by the pirates, and during the

plunder of the city in 1586, the cathedral was set on fire.

In 1566, the Spanish Crown enforced the rules called as the

Spanish Treasure Fleet or West Indies Fleet (Flota de Indies) as

a measure to prevent the attacks of the pirates to the

commercial ships that run to an appalling degree. According to

the new rules, all ships departing from the ports of the New

World that were under Spanish dominance, should arrive first in

Havana, and then to sail to Spain under convoy. The castle of

Havana was fortified to overcome this task. The increasing

traffic of the commercial ships led to the increase of the

population of Havana and the development of various branches of

business in the city and made a peak in the economics of the

area.

Although Santiago de Cuba has lost its

leading position to Havana, the unfavorable conditions forced

the government to divide the island into two administrative

regions, so that Santiago de Cuba remained as the capital

city

of the province Oriente until the 17th century (from 1522 to

1589). During this period, buffeted by severe earthquakes and

pirate attacks, the city developed more slowly compared to its

western rival, Havana, but most of the colonial architecture

that remained in the heart of the city as the emblematic

buildings, was built during this era.

By 1570, many Spanish men began to live with local women in the Spanish colonies on the island, because the number of Spanish women who came to the island with the Spaniards was very few. Over time, a mixed population developed, consisting of people of Spanish origin, people brought to the island as slaves from Africa, and the original natives of the island. Even though the Spaniards represented a superior stratum, there were no sharp boundaries between those of Spanish descent and those of indigenous descent. Those brought from Africa were closer to the Spaniards in terms of social status than the indigenous people of the island. This change in social life was more evident in Santiago de Cuba.

With the growth of the maritime transport

in the Caribbean, the aggressive political and commercial

rivalry between Spain and England increased in the 17th century

and led to an intermittent conflict between Spain and England

that was never formally declared as a war. Towards

the end of the war in May 1603, Christopher Cleeve arrived in

the Caribbean in the large armed galleon Elizabeth and Cleeve

with some privateers. His “military expedition” was largely

funded by several merchants from London. His aim was to attack

Santiago de Cuba, because although it was Cuba's second largest

city, it had never been attacked by the British since the

outbreak of the war. Christopher and his men enter the

unfinished fort and the ravelin without encountering any resistance. Even though

they encountered weak resistance when entering the city, they

plundered the city easily. Among the many buildings looted was

the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of the Assumption. Thus,

Christopher and his men captured a significant amount of loot.

Christopher, who occupied the city, demanded a large amount of

ransom, saying that otherwise he would set fire to many

buildings, including the cathedral. However, he didn’t receive

any answer. Thereupon all the fortifications in the city were

destroyed and many ships in the harbor were plundered and

burned. Christopher, who stayed in Santiago de Cuba for less

than a week, destroyed most of the city and left the city,

leaving his loot behind.

With the growth of the maritime transport

in the Caribbean, the aggressive political and commercial

rivalry between Spain and England increased in the 17th century

and led to an intermittent conflict between Spain and England

that was never formally declared as a war. Towards

the end of the war in May 1603, Christopher Cleeve arrived in

the Caribbean in the large armed galleon Elizabeth and Cleeve

with some privateers. His “military expedition” was largely

funded by several merchants from London. His aim was to attack

Santiago de Cuba, because although it was Cuba's second largest

city, it had never been attacked by the British since the

outbreak of the war. Christopher and his men enter the

unfinished fort and the ravelin without encountering any resistance. Even though

they encountered weak resistance when entering the city, they

plundered the city easily. Among the many buildings looted was

the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of the Assumption. Thus,

Christopher and his men captured a significant amount of loot.

Christopher, who occupied the city, demanded a large amount of

ransom, saying that otherwise he would set fire to many

buildings, including the cathedral. However, he didn’t receive

any answer. Thereupon all the fortifications in the city were

destroyed and many ships in the harbor were plundered and

burned. Christopher, who stayed in Santiago de Cuba for less

than a week, destroyed most of the city and left the city,

leaving his loot behind.

In the first quarter of the 17th century the British were seriously threatening the Spanish colonies. The Spanish that were losing the naval supremacy day by day, came to the decision to fortify their settlements. The attacks of the pirates in 1635 and in 1636 had a marked influence on this decision. Until that time the defense system of Santiago de Cuba consisted of Fort of Hernando de Soto (El Fuerte de Hernando de Soto), that was in the area where the Balcón de Velázquez is located today, and the ravelin, El Rivelin La Lengua del Agua, that was built on the narrow promontory at the entrance of the Bay of Santiago de Cuba. Fort of Hernando de Soto, built between 1539 and 1550, and then equipped with cannons, was the lookout point for incoming ships. For years the ravelin served to control the maritime traffic of the Bay of Santiago de Cuba. Consequently, Castillo de El Morro was built on the high cliffs on the promontory. The chosen place, where the Bay of Santiago de Cuba opens to the Caribbean Sea by a narrow channel, was the most favorable point to build a castle to protect the city from the British invasion. It would also function to ward off the pirates.

The construction of the stone fortress, integrated with the existing ravelin, begun under the direction of the famous Italian military engineer and architect Juan Bautista Antonelli in the time of the Governor Pedro de la Roca y Borja in 1633. Therefore, the castle was given the name El Castillo de San Pedro de la Roca, but the folk espoused the name of El Castillo de El Morro rather than its official name, as it was more meaningful and easier to call it by its localization, the promontory of El Morro. The construction of the castle finished in 1638.

Despite the indomitable appearance of the castle, in 1662 the English Vice Admiral Sir Christopher Myngs, who had a dirty career and also known as pirate, captured the castle after discovering, to his surprise, that it had been left unguarded. The city fell easily, and this success brought much loot to the pirates. The famous English pirate Henry Morgan that was under the command of Myngs at that time, stole the bells of the cathedral after plundering the temple and setting its chapel on fire. In same year the castle was destructed after an attack of the British navy; it was rebuilt in 1663 and subsequently expanded in 1669. Thanks to the refortification of the castle, an attack by a French squadron in 1678 was prevented. In the same year, the attack of nearly 800 bandits led by Pierre de Frasquenay, who ravaged the Antilles, was foiled.

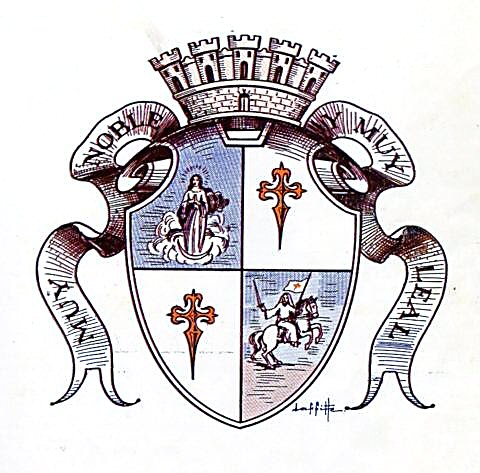

The depredations

that the city was suffering by the pirates, led the santiaguero

authorities to use the same method with the pirates. Several

governors of Santiago de Cuba authorized some santiaguero groups

to go out when a ship appeared on the horizon, fight and return

with the booty. These santiaguero corsairs played an important

role in the defense of the city. In 1704, when Don Juan Barón de Chávez, head of the government,

heard that the British navy was enlisting military people in

Provincia and Siguatey islands belonging to the archipelago of

Bahamas to attack Santiago de Cuba, he gathered 150 men, mostly

of santiguero corsairs, and made a raid on the British forces

that were not expecting such an attack. Chávez returned to

Santiago de Cuba with a great triumph and considerable booty,

consisted of guns, boats, and weapons. Consequently, the Spanish

king Felipe II granted the city the title “muy noble y muy leal

/ very noble and very loyal” by a Royal Decree on February 14,

1712. It is the first title that Santiago de Cuba received.

The city suffered severe damages by the

consecutive earthquakes during the period of 16th and 18th

centuries, but the city repaired itself each time. The Spanish

took the advantage of the opportunity to incorporate the most

recent developments in the architecture into the rebuilding

process of the important buildings like the cathedral, castle

etc. After the fortification, the Morro castle became the

fundamental link of the defensive system of the coast during the

colonial time, not only against the British navy, but also

against the corsairs and the pirates that plunder the Caribbean

in the 18th century.

The depredations

that the city was suffering by the pirates, led the santiaguero

authorities to use the same method with the pirates. Several

governors of Santiago de Cuba authorized some santiaguero groups

to go out when a ship appeared on the horizon, fight and return

with the booty. These santiaguero corsairs played an important

role in the defense of the city. In 1704, when Don Juan Barón de Chávez, head of the government,

heard that the British navy was enlisting military people in

Provincia and Siguatey islands belonging to the archipelago of

Bahamas to attack Santiago de Cuba, he gathered 150 men, mostly

of santiguero corsairs, and made a raid on the British forces

that were not expecting such an attack. Chávez returned to

Santiago de Cuba with a great triumph and considerable booty,

consisted of guns, boats, and weapons. Consequently, the Spanish

king Felipe II granted the city the title “muy noble y muy leal

/ very noble and very loyal” by a Royal Decree on February 14,

1712. It is the first title that Santiago de Cuba received.

The city suffered severe damages by the

consecutive earthquakes during the period of 16th and 18th

centuries, but the city repaired itself each time. The Spanish

took the advantage of the opportunity to incorporate the most

recent developments in the architecture into the rebuilding

process of the important buildings like the cathedral, castle

etc. After the fortification, the Morro castle became the

fundamental link of the defensive system of the coast during the

colonial time, not only against the British navy, but also

against the corsairs and the pirates that plunder the Caribbean

in the 18th century.

(1585-1604), unknown artist

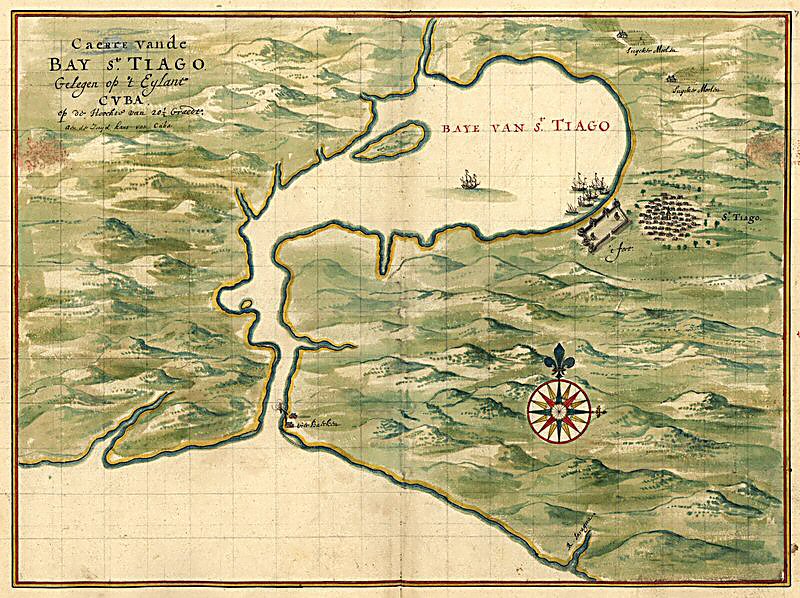

This map of Santiago de Cuba, created by Dutch

cartographer and engraver Joan Vinckeboons in 1639, is part

of the Henry Harrisse Collection in

Library of Congress